When Past Success Becomes Today’s Execution Problem: Understanding Path Dependency and Organizational Lock-In

Understanding Path Dependency

Organizations rarely struggle because leaders lack ambition. More often, execution breaks down because leaders stay attached to decisions, structures, and behaviours that once produced success. What worked in the past becomes the default answer for the future, even when conditions have fundamentally changed. This isn’t just a habit or resistance to change. It reflects a deeper pattern known as path dependency: earlier choices shape what leaders see, which options feel possible, and how the organization moves.

Path dependency is subtle because it rarely announces itself. It shows up in routines that no longer create value, in structures that once brought clarity but now create friction, and in stories about “how we do things here” that limit the ability to adapt. Over time, these patterns harden into organizational lock-in, where teams continue along a familiar path long after the environment and internal realities have shifted.

Leaders often label this as an execution problem—a lack of effort, accountability, or discipline. In many cases, the issue is more fundamental: the organization is executing a strategy that no longer aligns with either the environment it faces or the internal realities required to deliver it. When leaders rely on earlier models of success, they unintentionally narrow their sense of what is possible. The result is not immediate failure, but gradual misalignment, where the distance between strategy and results widens—quietly at first, then visibly all at once.

How Paths Form Inside Organizations

Organizational Path Dependence: Opening The Black Box, Academy of Management Review, Jörg Sydow, Georg Schreyögg and Jochen Koch, 2009

Path dependency begins with an initial set of decisions—about markets, technologies, structures, or ways of working. These early choices create increasing returns: the more the organization invests in them, the more costly it feels to change course. Systems, skills, and relationships are built around the original path. Over time, these investments generate a sense of inevitability: “This is who we are. This is what we do.”

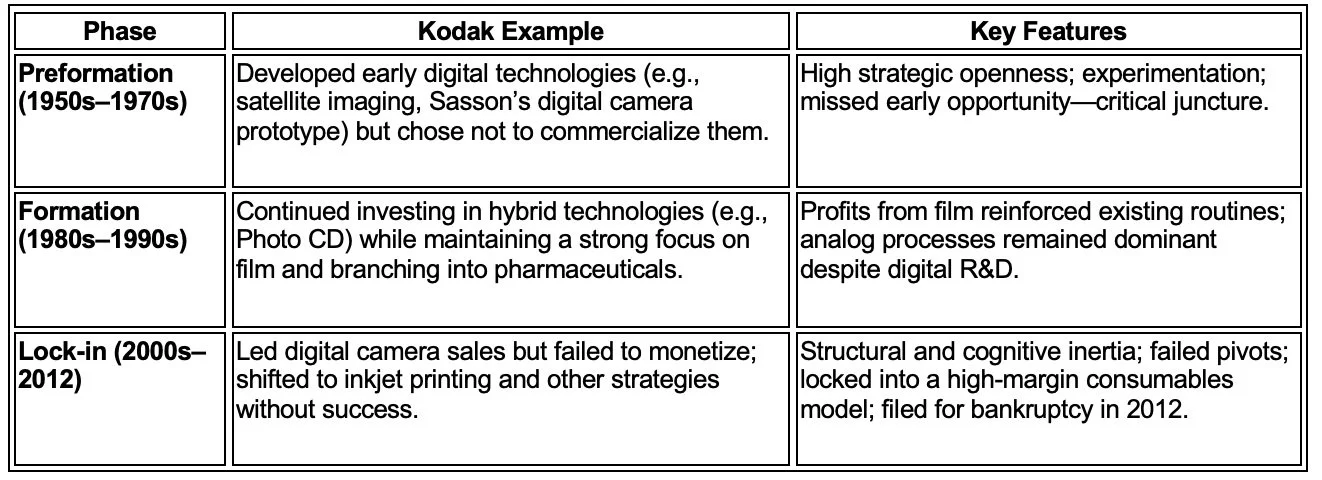

As the figure above illustrates, organizational paths typically evolve through three broad phases:

Path formation – Initial decisions and investments create a direction of travel.

Self-reinforcement – Routines, structures, and successes build around that direction.

Lock-in – Alternatives become harder to see and harder to justify, even when they may now be better suited to current conditions.

When Success Starts to Narrow Options

Because paths often originate in success, they are reinforced emotionally as well as structurally. A strategy that once accelerated growth becomes the mental template for every new opportunity. A structure that once helped leaders move quickly becomes a constraint that slows decision-making. Leadership behaviours that once inspired confidence become blind spots that limit judgment.

A Familiar Story: Kodak and the Cost of Staying on the Path

Kodak’s Surprisingly Long Journey Toward Strategic Renewal: A Half Century Exploring Digital Transformation in the Face of Uncertainty and Inertia, The Wharton School, Management Department, University of Pennsylvania, Natalya Vinokurova and Rahul Kapoor, 2022

The Drift Between Strategy and Execution

Strategic drift rarely appears suddenly. It builds as the environment evolves and internal realities shift, while the organization’s path continues along earlier assumptions

Recognizing and Unlocking Organizational Lock-In

Lock-in is not broken by adding more initiatives on top of the old path. It is broken by re-examining the conditions that keep the old path in place.

The Work of Letting Go

Path dependency reminds us that organizations rarely drift because of one decision. Drift emerges because earlier decisions continue to shape behaviour long after their relevance has faded. Leadership is not simply about choosing a direction. It is about continually testing whether the direction still fits the environment and the organization.

1. Clio and the Economics of QWERTY, The American Economic Review, Paul A. David, 1985 2. Organizational Path Dependence: Opening The Black Box, Academy of Management Review, Jörg Sydow, Georg Schreyögg and Jochen Koch, 2009. 3. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems, Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, C.S. Holling, 1973. 4. Kodak’s Surprisingly Long Journey Toward Strategic Renewal: A Half Century Exploring Digital Transformation in the Face of Uncertainty and Inertia, The Wharton School, Management Department, University of Pennsylvania, Natalya Vinokurova and Rahul Kapoor, 2022. 5. The Dominant Logic: A New Linkage Between Diversity and Performance, Prahalad and Bettis, 1986, 6. Managing the Unexpected: Assuring High Performance in an Age of Complexity, Weick K.E. and Sutcliffe K.M., 2001, 7. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams, Edmonson, A. C., 1999, 8. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective, Argyris, C. and Schön, D. A., 1978 and 11. Ambidextrous Organizations: Managing Evolutionary and Revolutionary Change, Tushman, M. L. & O’Reilly, C. A., 1996.